It is sunrise on mount Muhabura, an inactive volcano on the Ugandan-Rwandan border, and Dr Benard Ssebide is in a rush to find a family of mountain gorillas before the tourists arrive. A mass of ferns, vines and thistles encroaches on the path, and the guides hack through brambles with machetes. Above, the forest whistles in the wind, glowing in the morning light.

“The higher you go, the more the mountain pushes back,” Ssebide says, pausing for breath.

After nearly 45 minutes, a ranger spots patches of flattened grass and large piles of fresh, dark green dung. We are close.

Then the forest suddenly opens up to nine mountain gorillas – the Nyakagezi family – having their breakfast in a clearing. The enormous silverback munches his way through a thistle, throwing his visitors an indifferent glance.

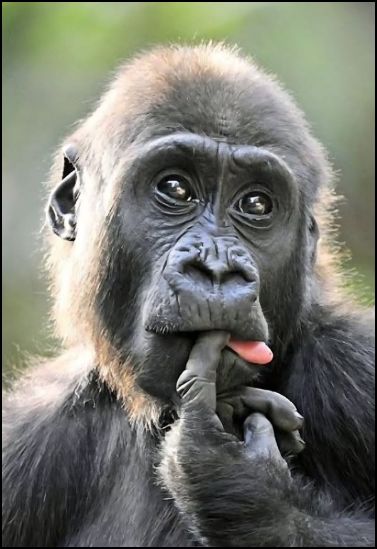

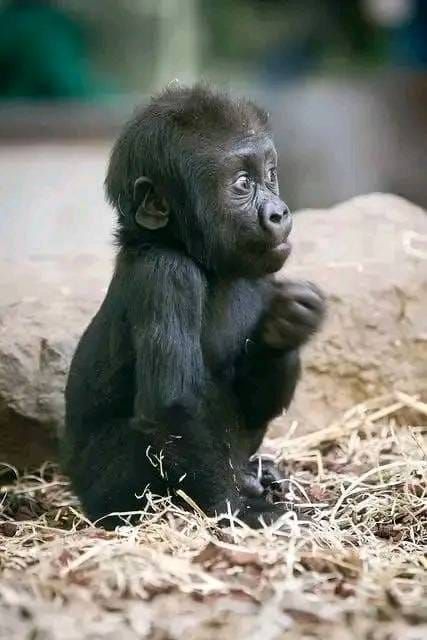

Nearby, a three-year-old juvenile swings on a vine watched by its mother. An adolescent male tugs at a wild blackberry, carefully picking off leaves to eat and grunting with satisfaction.The Virunga mountains, which range over the border region of Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), is one of two remaining homes for this endangered gorilla subspecies, identifiable by their thick fur and stocky frames that help them withstand the harsh conditions.

In the dense jungle of Muhabura, Ssebide, from the conservation organisation Gorilla Doctors, and his colleagues Dr Nelson and Dr Fred get to work. From a distance, they check the health of each animal, paying close attention to any signs of sickness or injury.

“They are all feeding well,” he whispers.

Gorilla Doctor vets, who work across all three countries, are key to the turnaround in mountain gorilla numbers, one of the greatest conservation success stories of the past century.

One study attributes half of the increase to the vets and their preventions of dozens of deaths, enabling the population to slowly grow.

“We have relationships with so many gorillas. Mark [this family’s dominant male] is just one. There are others. There is another born at Christmas in 2000; I saw him as a baby – now he is a silverback leading his own group,” Ssebide says.

When the Gorilla Doctors first started, much of their time was dedicated to dealing with injuries from the primates becoming caught in or lacerated by traps meant for buffalo and antelope in the forest.

Now respiratory diseases passed from humans have become a bigger problem. Anyone observing the animals now must wear a mask, disinfect their hands and keep their distance.